Shelagh Keeley: Drawn to Place

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

MARC MAYER

JAN 28, 2024

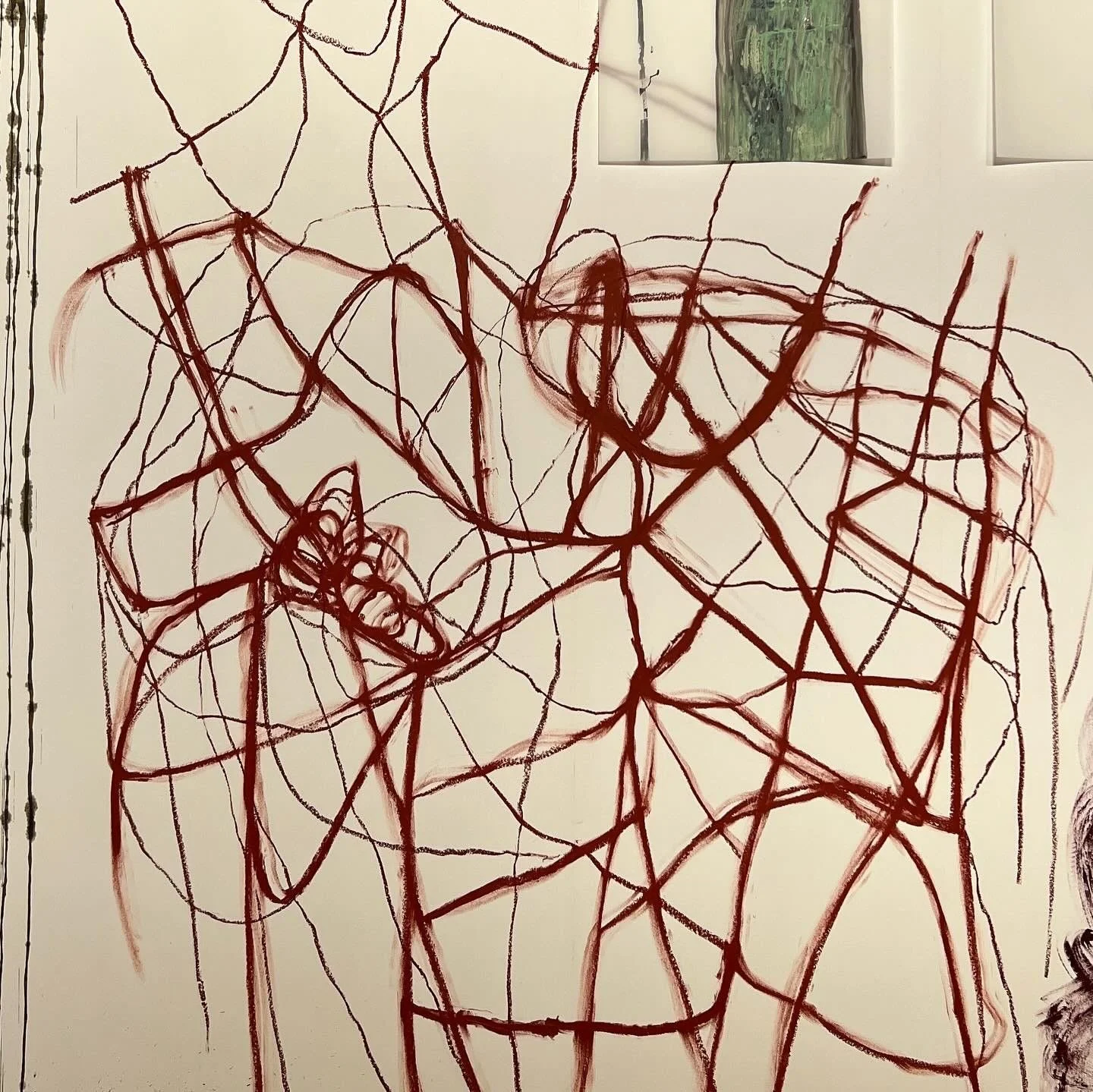

Installation view of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

Detail of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

When I was a kid, I hung out in a pool hall with my buddies. Not being competitive, I lost interest in pool early on to become an avid pinball player instead. But you can’t be too avid at pinball because of the dreaded TILT mechanism; if you get physical with the machine, the play stops, the lights die, and the ball is lost. Almost certainly inadvertent, TILT had a civilizing effect on us hyperactive boys, pulling energy from our bodies and funnelling it into our index fingers. My body still remembers how that felt.

Shelagh Keeley’s wall drawings achieve the same goal, but in reverse: they start the brain off at tilt, and require the whole body’s involvement to assimilate the thing beheld. Her wall drawings can be tough for the average viewer, but if you are able to follow the artist’s instructions and let your body do the thinking, you stand a good chance of beating the average. Pleasure here is not only intellectual, but physical.

Detail of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

You need the body’s involvement because Keeley monumentalizes the private activity of note-taking. Her wall drawings, which are also heavily collaged in the manner of scrapbooks, —smaller drawings, photocopies, photographs, etc.—require the full range of her musculature to create. They retain the notebook’s intimate character but at the scale of public art, so your eyes disperse the stimulus of their scale back into the body as your mind recreates the gestures of their making in the process of assimilation.

They start off by overwhelming you, as if they were beyond understanding, but that’s only a first impression. Experience with contemporary art teaches you not to trust first impressions. Firstly, like the humans who make the art, it can be more complex than even its makers can grasp. In fact, obscurity is often job one because it increases the use value of the work. Why keep looking at something you already “got”? You could look at this wall indefinitely, and it would continue to reveal mysteries.

A Keeley wall functions as a ‘time-out’ for the institution it addresses, “tilting” the place long enough for the viewer to glimpse its meta-significance. Unlike so many of her colleagues, Keeley does this not to articulate a critique of a given museum, library, or school, but as its lover, a physical and ardent one. Her originality is thorough.

Detail of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

The august Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), and particularly its Phillips Library, are the object of Keeley’s sensual ministrations. They’re both old by American standards, indeed the oldest in the case of PEM, founded in 1799 to house choice souvenirs of global maritime trade. The title of the show, of which the wall is the show-piece, is Drawn to Place. Keeley was drawn to PEM because of an affinity with what it has become over the centuries, a place where cultures brush against cultures, ideas against ideas. Keeley launched her career in the 1970s with a fully-formed transcultural sensibility, having first been drawn to anthropology. Visiting PEM must have been love at first sight. A notable strength are its objects from Japan, a country Keeley knows well for having shown there frequently over decades. PEM is an art museum born before ‘fine art’ took centre stage. Keeley’s wall is an artist’s genuflection to the living relevance of such old places and the old things that they harbour.

The Phillips Library was born as a repository for ships’ logs to eventually become the papered adjunct of the larger transcultural institution, so an ‘organ of transmission’ for someone who draws. Keeley’s wall begins and ends with books, but the centre is dedicated to the sorts of reflections that books ignite, for example on the essence of things that places like PEM collect. Helpfully, a selection of things that she enjoyed finding there is included in the show.

Insect cages and an incense burner, 19th century, Japan.

Pop-up teahouse maquette from Sukiya ezu, before 1869, Tansai Nobutatsu

Detail of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

There is a passage in the wall drawing that evokes the struggle to invent weaving, which is preliminary to the idea of cloth or basketry. Keeley’s work helps me understand the real meaning of ‘primitive,’ not the racist notion based on the false belief that there are primitives among us. ‘Primitives’ died out tens of thousands of years ago. Keeley’s primitive is the likely female hominid who first experienced the cognitive leap that led to drawing, that led to weaving, and eventually to AI, which was born of computers inspired by looms. What was it like to realise that nature was not only a trove of creature sustenance, but of tools? What was it like to realise that the body—legs, arms, hands—could be an instrument of thought? Great art can draw us back to the ur-moments of cognition. Keeley’s originality is thorough.

Stills from Kyoto Notebook, 1985, Super 8 film, 108:10 mins.

Drawn to Place, curated by the gifted Trevor Smith, includes the artist’s first film, projected in PEM’s Japanese galleries on the back of a tokonoma. That’s an elevated nook to display art in the home: a vase, a hanging scroll, or an ikebana arrangement. They evolved from Buddhist prayer alcoves, so Keeley’s views of Kyoto fit well because the film is meditative and beautiful. Her old friend, the late Michael Snow, is pictured reading in her wall drawing. He too made films, and they came to mind a time or two as I watched this one. And they too might bewilder someone struggling to understand, in this case, why such grainy tourist footage would be shown in an art

Michael Snow, reading, a detail of ideas brushing against ideas/the library as refuge, 2022.

museum. I should not be amused by such struggles but, shamefully, I am. For starters, there are no mugging children or adults with false smiles in the film. In fact, there are few people. It’s a gathering of details that the artist brushed against virtually, visual sensations judged worthy of noting on a walk through places that were new to her. Kyoto Notebook has gained an added frisson since it was shot in 1985 because it would be impossible to make today; regulations have since forbidden recording in some places.

The camera pans a lot with a slight hand-held wobble, and with a subtle pulsation during extended pauses on things she wants to fathom. I think of this film as an older sibling of her wall drawing, both of them engaged in a danced form of note-taking. We are aware that the camera was held by someone breathing, moving and thinking with her body. Although we never see her in the film, she is the one who walks, pivots, cranes, zooms and returns to puzzle once more over a novel detail, or over something too beautiful to pass by in haste. A long close-up of a No performer, whose automatic paces could have been choreographed by Bruce Nauman, is followed by a close-up of a baseball player projected on a proto-Jumbotron with big pixels. The segue had me understanding how the Japanese came to invent baseball, but of course they did not. “Ideas brushing against ideas.” Ryoanji, the rock garden of raked gravel fame, gets at least three changes of cartridge, which it merits. The film records Keeley’s struggle to escape the place.

Happily, the catalogue for a show that lingers sensually in the mind is an object of intelligent originality. It is exactly what one would hope for to honour an artist enamoured with books and a noble souvenir.