Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy

February 22 - July 10, 2022

Los Angeles, USA

For centuries, the structure of the human body was a fundamental concern for both medicine and art. Anatomy was a basic component of artistic education, and artists were a recognized part of the market for anatomical illustration. At the intersection of art and science, this exhibition looks at the shared vocabulary of anatomical images and at the different methods used to reveal the body through a wide range of media, from woodcut to neon.

It Takes Artists and Scientists to Understand the Human Body

A new exhibition explores depictions of anatomy from the Renaissance to today.

As a medical student at the University of Bologna in the late-18th century, you might have strolled home through the covered arcade of the Portico del Pavaglione, nipped into the printmaker’s shop owned by Antonio Cattani and his partner Antonio Nerozzi, and bought anatomical prints that mapped the body in actual size.

Aspiring painters were also among the shop’s customers since the prints were initially marketed to them; anatomy was a basic component of artistic training, and art students could consult the prints during life drawing classes to quickly resolve questions of form and contour.

In 2014 the Getty Research Institute (GRI) acquired three life-size figures by Cattani. These rare works, made up of five joined prints each, show figures based on anatomical sculptures by the Bolognese painter and sculptor Ercole Lelli. Two of these, carved of wood, still flank the lecturer’s seat in the University of Bologna’s anatomy theatre and were well known to any student attending a dissection. Cattani’s figures also feature in Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy, an exhibition exploring different methods of representing anatomy from the Renaissance to modern day. From impressive life-size illustrations to delicate paper flaps that lift to reveal the body’s interior, Flesh and Bones explores the body’s structure through a range of media. These often visually arresting images both instruct and evoke wonder and curiosity about the human body.

The Dance of Death, slain soldiers, and other inspirations

Artists were not only part of the market for anatomical images, they also helped create them. When anatomists (biological scientists who study anatomy) collaborated with artists to create anatomical illustrations, the ephemeral nature of the subject matter—human bodies that would quickly decompose—necessitated that an artist be close at hand. We know that the Paduan anatomist Giulio Casseri had an artist, Josias Murer II, living in his house for this purpose in 1593. Later Casseri worked with painter and engraver Odoardo Fialetti and engraver Franceso Valesio. Their illustrations in Casseri’s posthumously published Tabulae anatomicae (1627) have an uncanny liveliness. Instead of lying inert on the dissection table, the body is shown alive and active in a landscape setting. The animated cadaver was an enduring motif in early anatomical illustration, owing much to the Dance of Death tradition.

The Dance of Death dates back to the late Middle Ages and features exuberant figures of death interacting with people of all ages and from every level of society, interrupting their life’s course and reminding them of their own mortality. In the exhibition, this is captured in a mix of humor and horror in the series of prints designed by the Renaissance artist Hans Holbein the Younger. An equal sensibility is at play in the gregarious Mexican Day of the Dead skeletons of an early 20th-century printed broadsheet by José Guadalupe Posada.

Painter and art theorist Gerard de Lairesse used a completely different approach in the illustrations he drew for the Anatomia humani corporis (1685), an anatomy atlas by the Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo: dead bodies in life-size sections. This dedication to realism would later inspire English physician and anatomist William Hunter, whose Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures (1774) spectacularly documents the stages of gestation from full-term pregnancy to conception.

Some anatomists were artists themselves, narrowing the gap between knowledge and representation by contributing their own illustrations. One noteworthy example is Andreas Vesalius, a Flemish anatomist and surgeon who had a brilliant career in Italy before becoming physician to Emperor Charles V.

Vesalius was in the habit of picking up a piece of charcoal and drawing on the dissection table itself to elucidate a point for his students. He published some of his teaching diagrams in the Tabulae anatomicae sex (1538) in collaboration with Jan Steven van Calcar, a North Netherlandish artist then working in Italy in Titian’s circle.

Calcar likely worked with Vesalius on a much more ambitious work, the magnificent De humani corporis fabrica libri septem or “On the fabric of the human body in seven books” (1543), a copy of which is held at the GRI. The book set a new benchmark for the number, quality, and size of its illustrations, and became the model for illustrated anatomy books to follow. Vesalius contributed some drawings for the Fabrica (as it is known), but relied on an unnamed artistic team to produce its hundreds of woodcut illustrations. For the famous series of muscle figures set in a landscape with towns and ruins in the distance, Vesalius worked side-by-side with his draftsman, suspending a dissected cadaver by a rope and pulley attached to a beam, thus allowing him to raise or lower the body and to turn and pose it.

Getting it right: anatomy books just for artists

In the 17th century, a new genre of anatomy book arose, one specifically for artists that focused on the bones and muscles—the structures most visible on the body’s surface. From the GRI’s exceptional collection of these books, one of the most attractive is Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux beaux arts (1812) by French army surgeon Jean Galbert Salvage. The illustrations—in which the muscles and contour of the body appear in red, the bones in black—are based on Salvage’s own drawings. Salvage was inspired by the much-admired antique Greek statue, the Borghese Gladiator. To better reflect what was considered an ideal representation of the human body, Salvage obtained bodies of soldiers in their prime who had died in duels, then dissected them to different levels and set them in the Gladiator’s pose. The anatomical rendering of antique sculpture has the peculiarly forceful effect of presenting famous works in an unfamiliar yet still recognizable way, with the notion that beneath their surface lay anatomical layers to explore by picking up a chisel.

Before the mid-19th century, cadavers sanctioned for dissection were usually the bodies of those executed for crimes. Unofficially, though, bodies were stolen to help supply anatomy schools and private dissections, until laws like England’s Anatomy Act of 1832 regulated the supply of cadavers to include unclaimed bodies, often of the destitute. In 16th-century Italy, bodies for dissection were preferably those of executed criminals from outside the local community. Yet the souls of these subjects were still cared for, before and after death. Lay confraternities would escort the condemned to their execution site, comforting them, encouraging them to repent, all the while holding religious images before their eyes for their contemplation. Following their dissection, their remains were collected for burial with a service. (What appears to be a doodle in ink of a religious procession, perhaps recording one of these confraternities bearing away a body, can be found on the half-title page of the GRI’s copy of François Tortebat and Roger de Piles’s Abregé d’anatomie, accommodé aux arts de peinture et de sculpture, published in 1668 and dedicated to the Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture of France.) Similarly, many of today’s anatomy schools have memorial services at the end of the academic year for those who have donated their bodies for dissection, their families joining with the medical students to acknowledge their gift to further science.

Rivaling the impact of Vesalius’s Fabrica was the Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani (1747) by Leiden professor of surgery and anatomy Bernhard Siegfried Albinus. Unlike Vesalius, Albinus named his artistic collaborator, the Dutch painter and printmaker Jan Wandelaar (1690–1759) with whom he worked for decades on a number of illustrated anatomy books. Albinus controlled every aspect of the illustrations’ production, correcting Wandelaar’s drawings and prints where necessary. He wrote, “thus he was instructed, directed, and as entirely ruled by me, as if he was a tool in my hands, and I made the figures myself.” The elaborate backgrounds to the figures, filled with vegetation, rocks, architecture, water features, and in the case of two plates, a rhinoceros, were added at Wandelaar’s suggestion to promote a sense of the figures’ three-dimensionality. Upon publication, the illustrations were greatly admired for their accuracy, precision, and elegance. They soon became the standard images for anatomy and were endlessly copied not only by anatomists, but also artists. Their influence lingers even today. Next time you are at the California Science Center in Los Angeles, look for one of Albinus’s skeletons engraved on the DNA Bench in front of the entrance.

Today medicine relies on increasingly sophisticated ways to see inside the body. Visitors to the exhibition can experience a forerunner to the three-dimensional modeling of the digital age by viewing stereoscopic photography, a 19th-century technology used to convey an incredible sense of depth and immediacy to anatomical preparations. Also on view: books with layers of two-dimensional flaps that allowed a virtual dissection of the body in print, as well as an early book on X-rays. The discovery of X-rays at the end of the 19th century allowed people to see into the living body for the first time without disturbing its surface, launching a new revolution in the mapping of the body that had begun centuries before.

Exhibition Catalogue

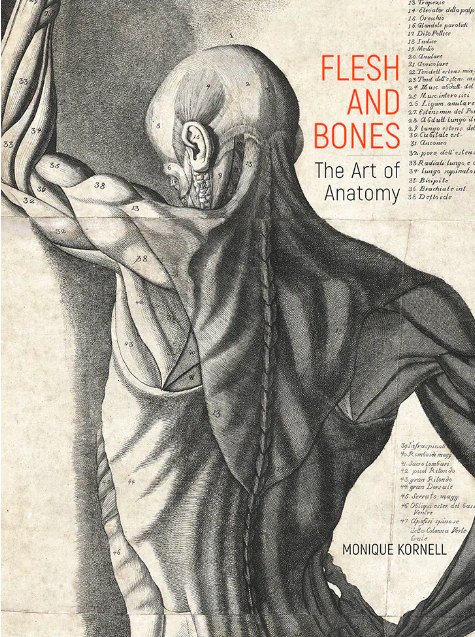

Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy

Monique Kornell

With contributions by Thisbe Gensler, Naoko Takahatake, and Erin Travers

This illustrated volume examines the different methods artists and anatomists used to reveal the inner workings of the human body and evoke wonder in its form.

For centuries, anatomy was a fundamental component of artistic training, as artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo sought to skillfully portray the human form. In Europe, illustrations that captured the complex structure of the body—spectacularly realized by anatomists, artists, and printmakers in early atlases such as Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica libri septem of 1543—found an audience with both medical practitioners and artists.

Flesh and Bones examines the inventive ways anatomy has been presented from the sixteenth through the twenty-first century, including an animated corpse displaying its own body for study, anatomized antique sculpture, spectacular life-size prints, delicate paper flaps, and 3-D stereoscopic photographs. Drawn primarily from the vast holdings of the Getty Research Institute, the over 150 striking images, which range in media from woodcut to neon, reveal the uncanny beauty of the human body under the skin.

This volume is published to accompany an exhibition on view at the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center from February 22 to July 10, 2022. Link to catalogue.